A few days ago, Adam Kissell published an essay in the American Mind, cleverly titled “New Koch.” In it, he describes the way in which the Charles Koch Foundation and related organizations such as the Institute for Humane Studies seem (to him) to have taken a leftward turn in recent years. As evidence he cites the fact that Koch organizations now talk about things like “breaking barriers” and “eliminating injustice” which, we all know, “are leftist buzzwords that signal openness to Critical Race Theory.” What’s worse, the folks at IHS are even have people reading and talking about ideas by critical race theorists. Imagine.

I found Kissell’s essay puzzling. Much of it seems to proceed on the assumption that ideas like “racial justice” and “creating a more equitable world” are inherently leftist concepts, anathema to Real Libertarians. But this just isn’t so. As a historical matter, as John Tomasi and I show in The Individualists, there has always been a significant (albeit inconsistently applied) egalitarian streak to libertarian thought, especially in its 19th century origins. And as a practical matter, if libertarians are going to announce that they have nothing to say about what many people regard as some of the most pressing matters of the day, they shouldn’t be surprised when they are consigned to political irrelevance.

Kissell’s essay, perplexing as it may be, is emblematic of the times. Libertarianism today is in the midst of an identity crisis, one sparked by the collapse of socialism as a political and intellectual threat. For most of the 20th century, libertarians essentially defined themselves in terms of their opposition to socialism - a definition that allowed them to gloss over many of the divisions both among libertarians and with their sometimes political allies on the right. Now that socialism has largely disappeared, many libertarians are searching for a new core to their identity.

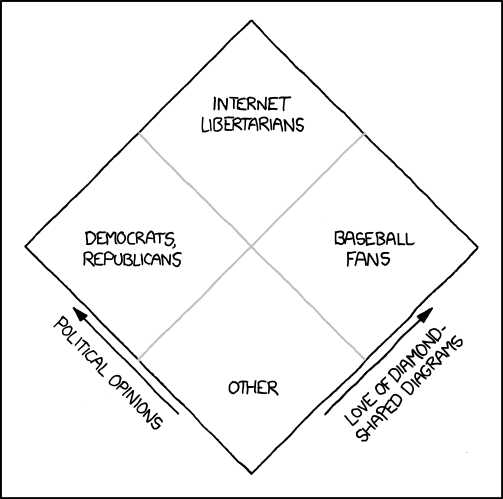

Some, like Kissell, are hoping to push libertarianism in a more culturally conservative direction. Others, resurrecting the paleo strategy of Rothbard and Rockwell, are moving in an even uglier, more populist direction. On the other side of the political spectrum, some people (like those of us at the old BHL and the people at C4SS) are arguing for a more progressive interpretation of libertarianism, seeking to connect libertarian ideas with concerns about social justice, equity, and empowerment.

So what is libertarianism? Is it a right-wing view? A left-wing view? Or is it neither? In an insightful review of The Individualists, Ari Armstrong proposed an alternative to the BHL (left) and paleo (right) interpretations of libertarianism. He calls it “BOL,” or “Boring Old Libertarianism.” BOL, according to Armstrong, is the kind developed by relatively mainstream libertarians over the course of the 20th century, in the tradition of “the Cato Institute, Reason magazine, the Ayn Rand Institute” and thinkers like “Mises, Rand, Friedman, and Hayek.”

BOL is a great label. And I understand the desire on the part of libertarians to distance themselves from both the left and the right. But I think the idea here rests on a mistaken assumption that there is some natural or neutral form of libertarianism, one that is only perverted by the addition of alien political, cultural, or moral values. There isn’t.

Libertarianism, as I understand it, is a family of political views built on a shared commitment to ideas like private property, free markets, skepticism of authority, individualism, negative liberty, and spontaneous order. But none of those concepts are self-interpreting. None of them wear their meanings on their sleeves. All require interpretation, and that interpretation is necessarily a value-laden process.

Here’s one example that we discuss extensively in the book. Take private property - arguably the core concept in the libertarian creed. But what exactly does it mean to be a supporter of private property? If A stole something from B 200 years ago, and then passed it down generation after generation to an innocent third party C, do we respect property rights by letting C keep it? Or by trying to find a descendent of B to whom we can make amends? Under what conditions - if any! - can individuals legitimately claim title to natural resources that (by definition) are not the product of any individual’s labor? Can we legitimately claim property in ideas? And what about pollution? If I start a fire on my property that blows smoke on to yours, is that a legitimate exercise of my property right? Or a violation of yours?

Answering these questions is less a matter of figuring out some pre-existing Platonic truth than it an exercise of judgment and choice. And that exercise will inevitably be informed by one’s broader philosophical commitments - one’s theory of human nature, one’s principles of ethics, and one’s sense of the kind of problems and opportunities that matter in the world and that one’s theory ought to address.

Libertarianism is thus a theory that can be developed in both politically conservative and politically progressive ways. And while all of us are tempted, at one point or another, to argue that only one of those interpretations constitutes the Real Libertarianism, I think this is a mistake, and largely a waste of time. The interesting question is not which version of libertarianism is the Real one. The interesting questions are about which version of libertarianism is best supported by philosophical argument and empirical evidence. And which points the way toward the kind of society for which we have the greatest reason to hope.

"So what is libertarianism? Is it a right-wing view? A left-wing view? Or is it neither?"

Here is one answer: https://jclester.substack.com/p/the-political-compass-and-why-libertarianism

I quite like the emphasis on judgment and choice, but it sort of risks blowing up the whole libertarian project. I think the sharp divides that were made apparent in 2016 show there's a pattern to the judgment and choice libertarians made, and *that* pattern is far more defining than whatever definitions we can come up with for libertarianism. In other words, whether you identify as a libertarian is basically meaningless next to the question of how you perceived Trump.