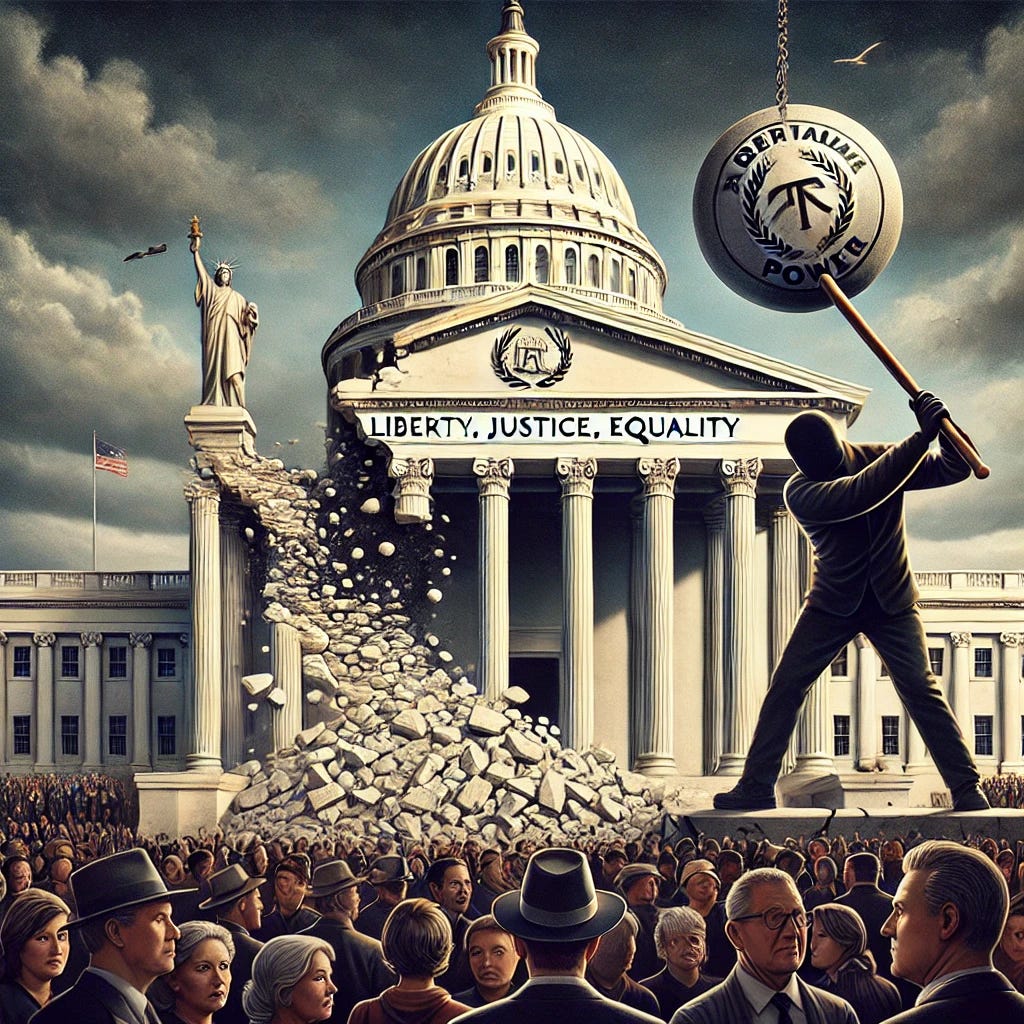

Libertarianism's Democracy Problem

Anti-democracy is the theory that the elites know what we want, and are going to give it to us good and hard

Like a lot of people these days, I’m pretty worried about the future of constitutional democracy in America. Whatever you think about the substantive merit of Trump’s policy agenda, the process by which he is pursuing it - a process that has so far involved the dismantling of bureaucratic expertise, attacks on the independent judiciary, attacks on the free press, and a general undermining of the separation of powers - should be deeply concerning.

A lot of libertarians, however, seem not to be concerned at all. In fact, many of them are positively reveling. As they see it, Trump and Musk are tearing down a system that is fundamentally corrupt. And if the methods they employ are somewhat unorthodox, well, what do you expect? The whole system is rigged against reform, so the only way to get the change we need is to operate somewhat outside the normal rules of the game.

The fact is, most libertarians just don’t think all that highly of democracy. This isn’t new. And they’re not that subtle about it. Book titles like Against Democracy and Democracy: The God That Failed don’t leave much room for guesswork even if, in the former case, the actual position advocated is a good deal more nuanced than the title suggests.

The libertarian aversion to democracy stems from two sources, which correspond to two types of libertarian moral framework. Some libertarians operate within a framework of individual rights, and believe the only legitimate government is one that is constrained to the protection of a narrow set of rights to life, liberty, and property. For these libertarians, democracy is at best instrumentally valuable, and at worst a threat to freedom. The only thing that matters is what government does - does it respect individual rights or not? The question of whether that government is democratically elected is beside the point. In Hayek’s notorious words, “it is possible for a dictator to govern in a liberal way. And it is also possible for a democracy to govern with a total lack of liberalism. I personally prefer a liberal dictator to a democratic government lacking in liberalism.”

Other libertarians take a more consequentialist approach, judging both markets and politics according to the outcomes they are likely to produce. For these libertarians, the problem with democracy is that it simply doesn’t “work.” Individual voters know their votes don’t matter, and so remain stunningly (but rationally!) ignorant about the most basic of political facts. And political institutions are captured by powerful special interest groups that have learned how manipulate the system for their own private advantage. Democracy is rife with rent-seeking, myopia, and other forms of “government failure.”

One group of libertarians sees democracy as fundamentally unjust. The other sees it as irredeemably inefficient. Both are all too ready to hand over the keys to a “liberal dictator” who promises to make government smaller and more rational. Especially if that dictator can portray himself as a Randian superman - the smartest guy in the room who is not afraid to speak truth to power and who will not sacrifice his individuality under pressure from the woke mob.

It is at this point that the libertarian disdain for democracy blends in to a lingering strand of elitism. Ayn Rand never quite entirely shook off her early Nietzchean phase, but nor was she unique in this respect. A similar idolization of the great man of genius is apparent in early libertarians and quasi-libertarians such as H.L. Mencken and Albert Jay Nock. It pops up in the anti-egalitarianism of Murray Rothbard (“Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature” is the revealing title of one of his essays). And it even, surprisingly, shows up from time to time in the writings of Friedrich Hayek. I say “surprisingly” because it seems that Hayek’s insights into the fundamentally dispersed nature of knowledge is one of the best arguments against epistocracy and other forms of elite political dominance. But here we are.

The problem with all of these anti-democratic arguments is not that they are wrong, exactly. The criticisms of democracy are valid. It really is unjust and inefficient, at least a lot of the time. The problem, of course, is that all the other systems are worse. It’s easy enough to imagine a system that might perform better. But constitutional democracy has a pretty impressive track record of actually delivering the goods when it comes to securing the blessings of peace, prosperity, and liberty. Democratic constraints undoubtedly limit the ability of well-intentioned, smart people to make sweeping reforms that make all our lives better. But they also limit the ability of those same well-intentioned, smart people (not to mention their less benign or intelligent fellows) to make all our lives remarkably worse.

Democratic institutions are some of the most effective tools we have for constraining power by, in the words of Madison, forcing “ambition to counteract ambition.” Libertarian critics of democracy sometimes argue as though the problem of power can be avoided if we simply shrink the size and scope of the state. But this, as Mike Brock has pointed out in damning critique, is to fundamentally misunderstand how power works. Power removed from the state does not magically evaporate into thin air. Instead, the removal of state power often simply opens up possibilities for that power to reconcentrate in private hands. (Check out Mike’s longer take on libertarianism and democracy here)

With all their talk of rent-seeking and cronyism, libertarians of all people should be sensitive to this point. And the better ones are. But at least in the popular movement, libertarianism often gets conflated with anti-statism, leaving a blind spot for the dangers of private, non-state power. However, as the late Steve Horwitz pointed out in a different context, being anti-state is not the same as being pro-liberty. And opposition to democracy hardly seems well-suited to either of these goals. For all its flaws, constitutional democracy remains our most reliable safeguard against the concentration of power—public or private—and our best hope for preserving true liberty in the face of the rising authoritarian temptation.

Mmm…democracy’s foibles could perhaps be addressed by severely limiting the power of rulers (not by entrusting epistocrats). I haven’t read Brock’s work (I will), but it seems to me that public power and private power are different in nature, for well-known reasons (externalities, incentives, etc.) that tend to make public power much more dangerous to liberty.

Even in a community made up entirely of people of good faith, you would want democracy as a conflict-resolution system. Communities have conflicts, because problems can be hard to solve, and because different values can come into conflict with each other. Democracy lets people try collective solutions with the assurance that if a solution doesn't work, it can be discarded in favour of a different solution later on.

A community consisting solely of good-faith libertarians would still have conflicts that would call for democratic resolution. As you've discussed in the past, private property and nonaggression are in tension with one another, and neither could reasonably be treated as an absolute value. An absolute commitment to nonaggression would make private property in physical goods impossible. An absolute commitment to private property would eliminate nonaggression as a libertarian value. Then there are hard problems, like what to do about negative externalities.

In my (outsider's) view, a lot of libertarian hostility to democracy comes from the dogmatic absolutism that is common in the community. People who think that you can derive the principles of ethics, politics and economics from a handful of axioms will usually fail to respect the validity of opposing viewpoints, and will tend not to see the value of a system of collective problem-solving and conflict-resolution that requires costly deliberation, moderation, humility and restraint.