Recently, I came across two different stories making the same important point. The first was in Ross Douthat’s fascinating interview with Marc Andreessen. In the course of that conversation, the question came up as to why Silicon Valley tech leaders like Mark Zuckerberg went along with the government’s demands to ramp up their fact-checking in the wake of “Russiagate.” Did they simply recognize that complying with the government was a necessary cost of running a profit-maximizing business?

Not according to Andressen.

The view of American C.E.O.s operating as capitalist profit optimizers is just completely wrong.

That’s like, Goal No. 5 or something. There’s four goals that are way more important than that. And that’s not just true in the big tech companies. It’s true of the executive suite of basically everyone at the Fortune 500.

I would say Goal No. 1 is, “I’m a good person.” “I’m a good person,” is wildly more important than profit margins. Wildly. And this is why you saw these big companies all of a sudden go completely bananas in all their marketing. It’s why you saw them go bananas over D.E.I. It’s why you saw them all cooperating with all these social media boycotts. I mean, the level of lock step uniformity, unanimity in the thought process between the C.E.O.s of the Fortune 500 and what’s in the pages of The New York Times and in the Harvard classroom and in the Ford Foundation — they’re just locked together. Or at least they were through this entire period…

These people aren’t robots. They’re just not. They’re members of a society. They’re members of an elite class. They either come from the top, most radical education institutions, or they are seeking as hard as they can to assimilate into that same class.

The second story comes from a really interesting lecture by the excellent Musa al-Gharbi. His topic is censorship in academia, and why so few conservative academics are willing to speak out in that setting. Is it that they’re afraid of getting fired? Or denied tenure? Partly, perhaps. But far more important than institutional censorship, according to al-Gharbi, is self-censorship. And self-censorship tends to be driven by a very different sort of concern.

When you look at polling and survey data about why people self-censor, the main thing that they're concerned about typically isn't formal sanction. They're not so much worried about being fired; they're not so much worried about getting bad grades. They are worried about those things, but the main thing that people seem to be worried about is social sanctions. They want to be included. They want to be liked. They don't want to be the person where they walk in the room and before they even start talking everyone's like, “Oh, God…” They want to get invited to things and … these these social concerns, these concerns about being liked and included and whatever seem to drive a lot of censorship and self-censorship.

These points caught my attention because I think they’re important both for understanding why people behave the way they do, and what we need to pay attention to if we want to change that behavior.

Economists like to say that people respond to incentives. And by “incentives,” they usually mean to refer to some kind of self-interest, whether narrow or “enlightened.” If incentives are what ultimately matter, then it follows that "institutions” (the humanly devised constraints that shape incentives) are going to pop out as the most obvious lever we have for changing people’s behavior. If you want more of some behavior, make it pay. If you want less of it, make it costly.

If you push really hard, you can cram the phenomenon of wanting to be liked until it fits into this model. But that’s probably not the easiest or most helpful way of understanding things. Wanting to be liked be others isn’t just one preference among a whole bunch of others, like a taste for chocolate ice cream, that we collectively refer to as a person’s “self-interest.” It’s something more fundamental and unique - something that competes with (and often defeats) self-interest as we usually understand it. And taking it seriously suggests that social change is at least as much a matter of culture as it is of institutions, as those are typically understood.

One final point. While al-Gharbi speaks of wanting to be liked, Andreesen’s point is about wanting to think of oneself (or to be thought of by others as) “a good person.” These are not the same. And the contrast between them naturally brings to mind Adam Smith’s famous line that “man naturally desires, not only to be loved, but to be lovely.” We don’t simply want to be liked by others; we want to be the kind of people who are worthy of being liked - i.e. we want to be ‘good.'

Fair enough. But while being loved and being lovely might indeed be conceptually distinct, they are often very hard to disentangle in the real world. After all, our beliefs about what counts as lovely are driven to a very large degree by what those around us happen to love. If everyone around you thinks that being a SJW is part of what it means to be ‘good,’ it’s going to take an unusual degree of independence for you to conclude otherwise. Even if you’re inclined to disagree, the pressures for rationalization and self-deception are going to be huge. If a big part of what you want is to be accepted by others, it’s easy enough to tell yourself a story about why their view about what’s lovely is actually correct.

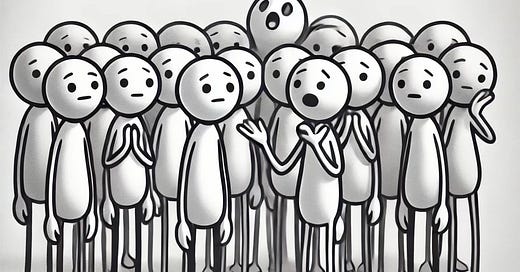

In other words, the pressures toward conformity are enormous.