Now that Trump has won the election, Lina Khan’s days as head of the Federal Trade Commission are almost certainly numbered. A lot of libertarians and conservatives are pretty happy about this. Khan is a committed leftist, with roots in Yale’s Law and Political Economy Project (see my earlier essay here). She has been an aggressive proponent of antitrust, using her position to closely scrutinize mergers and the market power of big tech corporations. Critics like Reason’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown argue that this has been bad for business and bad for consumers.

But I’m not so sure. On their face, a lot of Khan’s reforms seem pretty consumer-friendly. With “click to cancel,” Khan made the process of cancelling memberships and subscriptions easier and more transparent. Her ban on Non-Compete agreements has made life easier for workers and arguably unlocked new potential for entrepreneurship and innovation (see research by colleague Orly Lobel here and here). She even made it possible for owners of McDonalds franchises to repair their own ice cream machines, rather than forcing them to work with a monopolistic service provider. I mean, geez. What’s not to like about that?

But to understand the big picture of what Khan is up to, we need to dive a bit more deeply into her underlying philosophy of antitrust, as well as the seemingly more “free market” philosophy of antitrust she’s seeking to replace. I’m going to argue that while there might be some serious problems in Khan’s approach, the core of it is based on an important insight. It is, moreover, an insight that libertarians in particular should be able to appreciate.

A Very Brief History of Antitrust1

Back in the bad old days, the story goes, antitrust policy was relatively divorced from economic reasoning. Bigness was a problem, not primarily because of its effects on the economy but because of its effects on society. The key figure here is Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, whose 1914 essay “The Curse of Bigness” expressed concern about the effect of size not just on smaller competitors and prices, but on the healthy function of a democratic republic.

The Brandeisian approach to antitrust was dominant up to about the early 1970s, when it was overshadowed by the Harvard structuralist school and its “SCP paradigm.” SCP stands for “Structure, Conduct, Performance,” and holds that market structure (especially market concentration) leads to market conduct (e.g. anticompetitive behavior), which in turns leads to market performance (lowered innovation, higher prices, etc.). While the Brandeisian model saw antitrust as a kind of socio-political philosophy, structuralism cemented antitrust’s new role a a technical tool of economic regulation.

Then, in the late 1970s, the clouds parted, and Robert Bork descended from the Heavens. Bork’s 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox led scholars and practitioners alike to reject the structuralist framework, and to embrace a new vision of antitrust based on the standard of consumer welfare. He and his colleagues in the Chicago school of antitrust argued that the alleged relationship between structure and performance was nowhere near as tight as the structuralists had imagined. Highly concentrated markets were often a byproduct of economies of scale, not anticompetitive practices. But if bigness doesn’t necessarily make consumers worse off, then bigness as such isn’t really the problem. Antitrust policy, according to Chicago, should target only behaviors that actually reduce consumer welfare, and otherwise leave the market alone.

The Chicago view was profoundly influential on American antitrust law. Bork’s book was cited approvingly by the Supreme Court almost immediately after it came out, and the consumer welfare standard is still the dominant consideration in antitrust law today. As a result, government started to take a much more laissez-faire approach to mergers and acquisitions than it had for most of the twentieth century.

Market Coercion

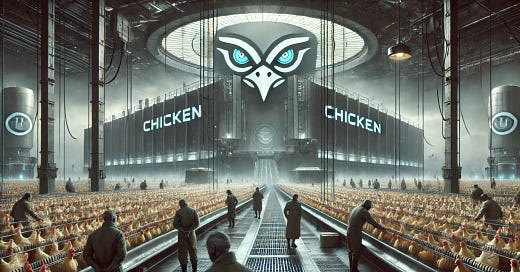

Then came Lina Khan. Long before Khan was appointed to head the FTC, she was a business journalist. One of her projects involved looking into the practice of chicken farming. According to Khan, the poultry industry is dominated by just a handful of processing companies. This means that farmers are often in a “take it or leave it” situation with respect to the processors, on whom they depend for their livelihood. About a decade ago, the federal government was running a series of listening sessions to learn more about problems faced by farmers in the industry. But many of the chicken farmers simply didn’t show up. The reason? The processors had threatened to retaliate against them if they did, and that was a risk they simply couldn’t afford to take. The processing companies were using their market power to silence workers, effectively undermining both their freedom of speech and their ability to improve their working conditions.

Stories like this aren’t unique to the poultry industry. And they aren’t exclusively told by those with left-wing sympathies. Todd Zywicki, a libertarian law-and-economics professor at George Mason University, tells the story of how he wound up suing his university when it tried to force him to get the COVID vaccine against his wishes. And he and many other conservatives have lately expressed growing concern about the power of big social media companies who seem to have used their power to silence or marginalize dissenting voices on issues pertaining to COVID, the Hunter Biden laptop story, and more. Conservative Texas even passed a law trying to regulate social media companies to prevent them from censoring based on viewpoint, which wound up in the Supreme Court earlier this year.

Now, in theory, market competition could handle all of this. If your university has rules you don't like, you can just quit and get a job at another one. If the big social media companies are silencing conservatives, just start your own and take their disgruntled customers. But in reality, we all know things aren’t that easy. Markets are sticky, network effects are real, and market processes take time to do their work. Meanwhile, while we wait for some new equilibrium to be reached, people’s livelihoods are being destroyed.

Neo-Brandeisianism

All of this brings us to Khan and her “neo-Brandeisian” approach to antitrust. Notice that none of the cases above are really about consumer welfare. They aren’t even about “bigness” per se. They are about power, specifically unchecked private power, and the coercion that such power makes possible.

For Khan, reigning in this power is the primary and proper goal of antitrust policy. She calls this a “republican” concept of antitrust, meaning that the highest goal of antitrust should be the protection of individual freedom. Importantly, “freedom” here means not being subject to the arbitrary will of anyone else - whether that person is a government bureaucrat or a corporate overlord.

So, for instance, here’s Khan approvingly summarizing Tim Wu, another neo-Brandeisian scholar of antitrust:

The analysis focuses on how having one’s life largely governed by unaccountable private power tends to undermine liberty and self-determination. “We like to speak of freedoms in the abstract, but for most people, a sense of autonomy is more influenced by private forces and economic structure than by government,” Wu writes, explaining that Justice Brandeis viewed “real freedom as freedom from both public and private coercion” (p. 41). The threat to liberty posed by monopoly — which can be understood as a form of private sovereign — remains a “major blind spot for contemporary libertarianism, which is rightly concerned with government overreach but bizarrely tolerant of mistreatment or abuse committed by so-called private actors.”

I’ve written with appreciation about the republican idea of freedom before and the role that it plays in Friedrich Hayek’s Constitution of Liberty. It’s not the same concept of freedom that you find in Nozick or Rothbard. But it is a deeply attractive one, and one that (as folks like Robert Taylor have demonstrated) can do a lot to support the ideals of free markets and limited government to which libertarians are attracted. That it might also provide a theoretical basis for limiting markets in cases where they fail to promote individual freedom seems to me to be a feature, not a bug.

So Why Only Two Cheers?

Endorsing a republican conception of freedom, however, does not automatically amount to an endorsement of activist antitrust policy. Even if we think that the protection of republican freedom is a worthy normative goal, it might turn out that antitrust policy is not the best way of achieving that goal.

For instance, one thing we want out of antitrust policy is clarity. A good system of antitrust should provide clear standards so that judges have some relatively objective factual basis for their decisions, businesses have clear expectations for how the law will respond, and opportunities to “game the system” are minimized.

Changes in prices or output are relatively easy to measure and assess. Changes in “coercion” or “freedom” or “fairness,” on the other hand, are notoriously difficult to pin down. And the more vagueness there is in antitrust standards, the easier it will be for powerful private actors to manipulate those standards for their own interest.

Moreover, as D. Daniel Sokol notes in his review of Wu, it’s easy to underestimate just how difficult is to anticipate how markets are going to develop, which winners are going to stay winners, and which minor players are about to make a big move. And with highly imperfect information, antitrust policy runs the risk of stifling dynamism and innovation, rather than facilitating it.

Maybe these concerns can be managed. Maybe not. I’m still making up my mind on this issue. But one thing I’m sure of is that libertarians should not be so quick to reject Khan’s approach simply because she is of the left. Private power is still power. And private threats to freedom are still threats to freedom. If libertarians want to be credible in their commitment to individual liberty, we need to take these issues seriously.

The history here draws heavily on Daniel Crane’s excellent essay, “A Premature Postmortem on the Chicago School of Antitrust.” My own presentation is grossly oversimplified and omits a great deal of complications and nuance for the sake of brevity and simplicity.

Hi Professor, one sub-topic of interest within antitrust would be that of antitrust immunity. On this front, you should have a look at the DOT’s granting of antitrust immunity to airlines that form ‘metal neutral’ agreements (Delta-Korean Air, United-ANA, AA-JAL). If you look at the decisions to grant antitrust immunity, a lot of the focus is on the purported market share that these firms will have. A problematic metal-neutral agreement which has received approval (though from the Competition and Consumer Commission Singapore) is Singapore Airlines-Air New Zealand where the two basically now have a monopoly over the Singapore-New Zealand route. Similarly, you might want to have a look into Singapore Airlines-Lufthansa and the near-monopoly they now share on the Singapore-Frankfurt and Singapore-Switzerland routes.